President Donald Trump is asking the Supreme Court to eliminate a key tool that lower courts have used to block various aspects of his agenda.

In an emergency appeal Thursday, Trump asked the justices to rein in or shelve three nationwide injunctions lower-court judges have issued against his bid to end birthright citizenship. But his request could have repercussions far beyond the debate over the controversial citizenship plan.

Judges have used nationwide injunctions to hobble many of Trump’s early moves, from his bid to end “Diversity, Equity and Inclusion” programmes to his cuts to federal medical research.

But Trump’s acting solicitor general, Sarah Harris, argued to the Supreme Court that federal district judges have no authority to issue sweeping orders that block policies nationwide.

Instead, Harris suggested, an injunction should apply only in the geographic district where the judge is located — or only to the specific individuals or groups that sued.

“Years of experience have shown that the Executive Branch cannot properly perform its functions if any judge anywhere can enjoin every presidential action everywhere,” Harris wrote, contending that while administrations of both parties have lamented the practice, it has reached “epidemic proportions” during Trump’s current term.

Lower-court judges issued 15 nationwide blocks of Trump administration actions in February, Harris asserted, although in some instances the same policy was blocked by multiple judges.

That one-month total outstrips the 14 nationwide injunctions issued against the federal government in the first three years of President Joe Biden’s term, she wrote, citing a law review study.

Lawsuits over birthright citizenship

The injunctions that triggered Trump’s emergency appeal were issued against his Day 1 executive order attempting to end birthright citizenship. That order seeks to deny U.S. citizenship to children born on American soil to parents who are undocumented immigrants or in the country on short-term visas.

Judges in Maryland, Massachusetts and Washington state separately blocked the order from taking effect nationwide.

They said it blatantly violates the 14th Amendment, which guarantees citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.”

Trump is not yet asking the Supreme Court to assess the executive order’s constitutionality. Rather, he wants the high court to narrow two of the injunctions and to lift the third entirely — a request Harris called “modest.”

“This Court should declare that enough is enough before district courts’ burgeoning reliance on universal injunctions becomes further entrenched,” Harris wrote.

The practice of individual federal judges issuing injunctions that completely halt a federal policy has drawn extensive and increasing criticism in recent years. Some legal academics have questioned them, and both Democratic and Republican administrations have fought them. Two Supreme Court justices — Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch — have openly doubted their constitutionality.

Critics say nationwide injunctions give district judges too much power and encourage administration opponents to file lawsuits in specific districts or even direct them to specific judges they think will be sympathetic.

But liberal and conservative groups who challenge federal policies say such injunctions are often the only efficient and fair way to address unlawful or unconstitutional government actions.

One difficulty with the vehicle Trump has chosen for his fight against nationwide injunctions is that courts have sometimes found them particularly appropriate in immigration-related cases, so that people traveling aren’t treated differently depending on where they encounter federal officials.

And a decision from the Supreme Court curtailing the lower-court nationwide injunctions in the birthright citizenship lawsuits could spur even more litigation.

A huge number of individuals potentially affected by the birthright citizenship policy might decide they need to file their own lawsuits, or join existing lawsuits, in order to protect their children from the policy.

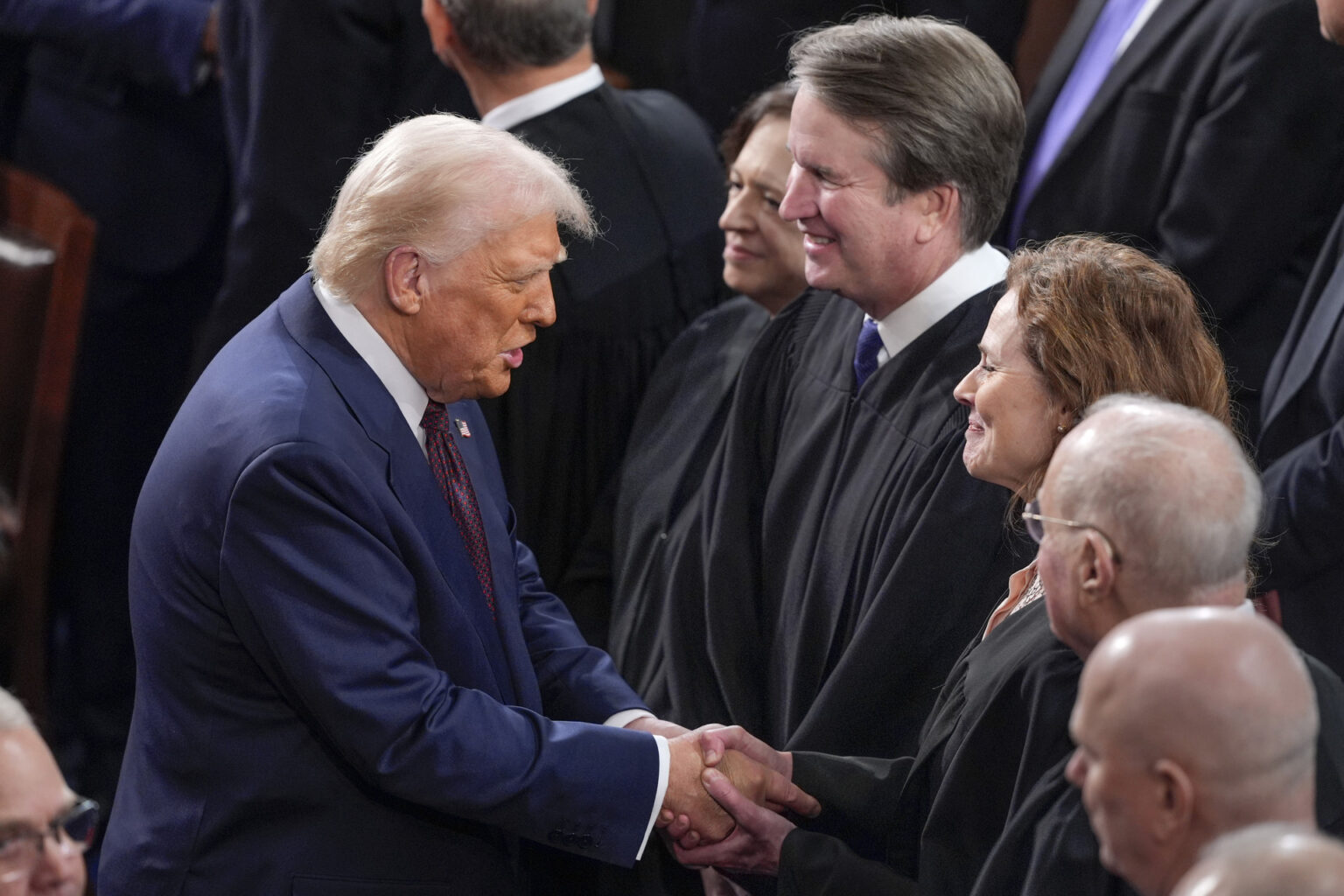

President Donald Trump greets justices of the Supreme Court Elena Kagan (left), Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, before addressing a joint session of Congress at the Capitol, March 4. | J. Scott Applewhite/AP

The Trump administration’s submission to the high court says those individuals could have their rights protected through class-action lawsuits.

However, the process used for such suits is cumbersome and time-consuming, making it unlikely they could win the swift relief that the judges ordered in the three existing cases.

Opposing state-led lawsuits

In addition to taking aim at nationwide injunctions, the Trump administration’s appeal to the Supreme Court seeks to weaken the ability of states to file lawsuits against federal policies.

States with Democratic attorneys general have brought a flurry of such lawsuits in the past two months, challenging Trump actions on issues ranging from transgender rights to safeguards on sensitive federal government data to reimbursement rates for federal grants. One of the injunctions blocking the birthright citizenship order came in a case brought by 18 blue states.

Trump’s Supreme Court filing argues that states don’t have the right to bring suits on behalf of their residents.

“States and their political subdivisions have inundated federal courts with politically charged suits challenging federal policies,” Harris complained, noting both that California’s Democratic attorney general had boasted of filing more than 100 lawsuits against the Trump administration during Trump’s first term and that Texas’ Republican attorney general had bragged of filing more than 100 suits against the Biden administration.