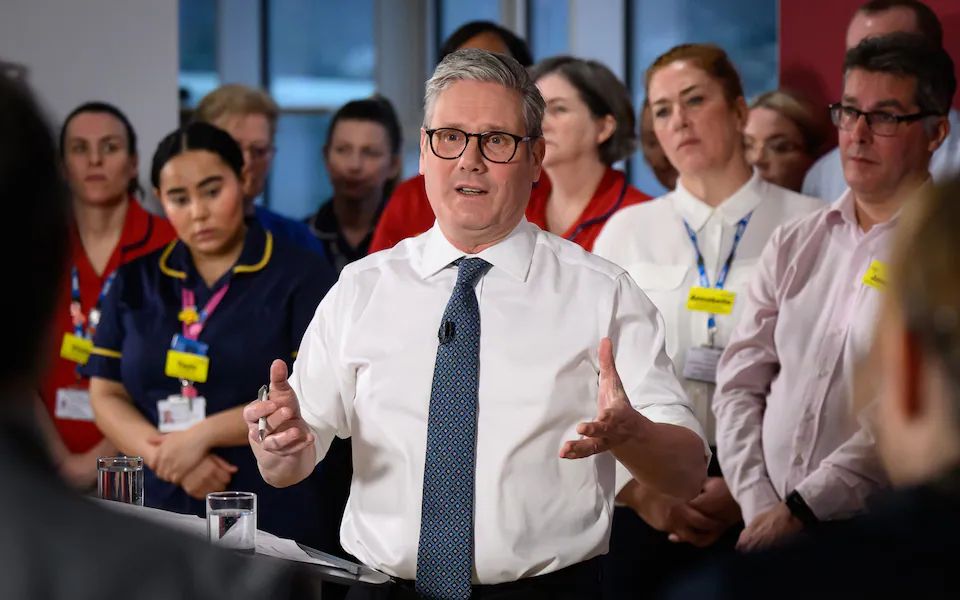

Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer will, on Thursday, unveil Labour’s 10-year health plan, pledging to create a six-day a week neighbourhood health service in what he describes as one of the most radical reforms in NHS history.

The new plan aims to shift routine healthcare out of hospitals and into local one-stop centres, offering care from GPs, nurses, dentists, and other professionals under one roof. These neighbourhood clinics would operate 12 hours a day, six days a week, providing access to diagnostics, post-operative care, rehabilitation services, and even social support like debt advice and employment coaching.

Starmer is expected to say the NHS must reform or die, warning that the current hospital-centric system is no longer sustainable. He will describe the plan as a way to fundamentally rewire and future-proof the NHS by bringing care closer to patients, embracing technology, and focusing on prevention.

Key features of the plan are six-day access, one-stop neighbourhood centres, staffing reforms, and community outreach.

Newly qualified dentists will be required to work in the NHS for at least three years, and the NHS app will become central to patient care, using artificial intelligence to direct users to appropriate services.

The proposal follows a difficult week for Starmer, who faced internal party unrest and was criticised for not publicly backing Chancellor Rachel Reeves. Labour sources hope this ambitious NHS announcement will mark a reset moment for his leadership.

The proposed model draws some inspiration from Australia’s community-based clinics and echoes Labour’s previous attempt to introduce polyclinics under Gordon Brown. That earlier plan failed after opposition from the British Medical Association. Similarly, Conservative pledges to deliver a seven-day NHS during the Cameron and May years never materialised and led to industrial disputes, including the first doctors’ strikes in decades.

This time, Labour hopes to avoid such resistance by giving top-performing GPs more autonomy to run larger centres across wider areas.

Still, critics argue that the proposals lack ambition compared to those earlier, failed promises. Dr Sean Phillips of the Policy Exchange think tank noted that access to out-of-hours care was better before 2004 and warned that vulnerable patients could be left behind by the digital-first approach.

NHS in Crisis

Twelve months after Labour’s general election victory, the NHS remains under severe pressure. The waiting list has only fallen marginally down by 200,000 to 7.39 million. A quarter of patients still wait over four hours in A&E, and just under 70% of cancer patients start treatment within the target time of 62 days.

Despite repeated pledges to improve access to GPs, fewer than 60,000 patients are seen at weekends, compared to 1.6 million on Mondays.

Health Secretary Wes Streeting insisted the plan would turn the NHS on its head, shifting focus from crisis management in hospitals to prevention and coordinated local care.

“With this plan, we will finally end the days of patients bouncing from pillar to post,” he said.

The government also plans to have the NHS spending watchdog, NICE, reassess medicines it has previously approved, and withdrawing support for those no longer considered cost-effective.

As the government prepares to launch its flagship reform, questions remain over how it will be funded and whether the vision can overcome the institutional and staffing challenges that have plagued past efforts.