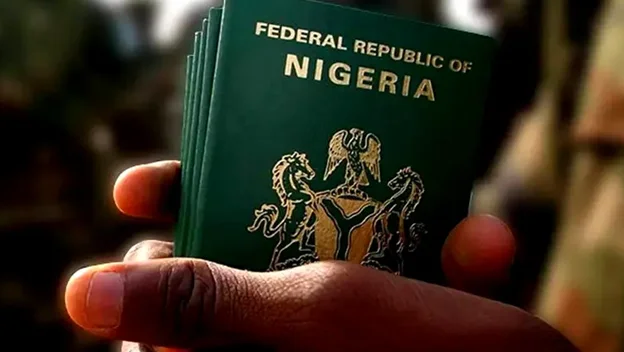

“Japa is becoming mission impossible.” This was all X user Sholzzola could type to vent his frustration after the Federal Government, through the Nigeria Immigration Service (NIS), announced yet another increase in passport fees—barely a year after the last hike. ‘Japa’ is a slang term for emigrating in search of better opportunities.

The new directive, which took effect on 1 September 2025, immediately drew widespread outrage. For many Nigerians hoping to travel abroad, the news felt like yet another roadblock.

Before the latest adjustment, the 32-page passport with a five-year validity had risen from ₦35,000 to ₦50,000, while the 64-page, 10-year passport had increased from ₦70,000 to ₦100,000. Now, the 32-page costs ₦100,000, and the 64-page has doubled to ₦200,000, figures many citizens describe as “wickedness” and a calculated attempt to deny the poor a chance at a better life

One X user, Chibuike Onowu, expressed his anger, saying: “How can a hungry man now pay for the least requirement for japa! To reduce japa rate, that’s the target.”

Echoing his sentiments, Oladejogab questioned the logic behind the hike: “The price just went up recently and now they are increasing it again.”

For Ojua_denis, the process of leaving Nigeria now seems almost impossible: “Travelling out is just getting harder daily.” Similarly, smart_onX quipped, “Doubling the price won’t double the service but will definitely double the complaints.”

And for Preshypeace, the development only sparked worry: “How do I want to renew my own at this exorbitant price?”

Expert Concern over Nigeria’s International Passport Price Hike

In an interview with the New Daily Prime, Dr Emmanuel Oluwole Oni, Investment Operations Executive at FNZ UK Ltd, warned that the hike would disproportionately affect low-income Nigerians who depend on passports to travel abroad.

Dr Oni explained that the increase was driven by several factors, including rising production costs, Nigeria’s local content policy, exchange rate fluctuations, and efforts to improve service delivery. He also noted enhancements in passport quality and compliance with international standards.

At the same time, he clarified that for many middle-income earners, business executives, and professionals, the new fees might pose only a minimal burden—particularly if the revamped passport system succeeds in eliminating unofficial costs such as bribes, which have long plagued the process in Nigeria.

Comparing the latest hike with previous ones, Dr Oni described the development as a “steep and troubling adjustment that risks widening the inequality gap.”

“In 2010, a 32-page passport with five-year validity cost N15,000. By 2018, when Nigeria introduced the enhanced e-passport, the fee rose to N25,000, a 66.7% increase. In 2023, it increased again to N35,000, marking a 40% rise over five years. In 2024, just one year into the current administration, the fee was raised to N50,000, a 43% jump. Now, from September 1, 2025, the cost will double to N100,000 representing a 100% increase in just one year,” he said.

Dr Oni stressed that this was the first time in Nigeria’s history that passport fees had doubled within a single year, and also the first time an administration imposed a hike just a year after the previous increase.

He questioned the official rationale for the adjustment, noting that explanations such as production costs, security enhancements, and administrative expenses did not adequately justify the rise.

Instead, he argued, the increase was primarily revenue-driven and introduced without regard for the burden on citizens.

He pointed out the irony that although the Nigerian Security Printing and Minting Company (NSPMC), a public institution, is mandated to produce passports, the task has instead been outsourced to Iris Smart Technologies Ltd, a Malaysian private firm, making Nigerian passports effectively a foreign commercial product.

The economist further observed that the Nigerian Immigration Service (NIS) had offered no evidence of significant upgrades in security features for the new passports, while administrative costs for processing remain covered under its budgetary allocations.

He also pointed out that since the last hike in 2024, the exchange rate had actually improved—undermining claims that rising production costs justified the latest adjustment.

From an economic perspective, Dr Oni explained that government-imposed fee hikes or subsidy removals function as indirect taxation, reducing citizens’ disposable income.

Nonetheless, he called for a measured understanding of the real impact. Unlike in many other countries where a passport is a crucial form of identification, in Nigeria it is largely regarded as a travel document, often referred to as the “international passport.”

As such, only those intending to travel typically apply for one. Given the country’s income disparities, the very poor rarely travel abroad, and for those who do, the passport fee is only a small fraction of their overall expenses.

This, he contended, means that the vulnerable—usually the focus of government policy—are not the group most directly affected. Instead, the burden falls on a narrower segment of the population: those who require passports for international mobility.

On potential benefits or trade-offs, Dr Oni dismissed any justification for the hike. He stressed that Nigerian passports already comply with the International Civil Aviation Organisation’s (ICAO) Document 9303, which sets minimum standards for biometric features, durability, forgery resistance, and global interoperability.

Since these benchmarks are already met, raising fees under the pretext of “quality improvements” was, in his view, indefensible.

Minimum wage proportion

Providing an international comparison, he argued that true affordability is measured not by the nominal cost of a passport but by its share of the monthly minimum wage. In Germany, the fee amounts to 3.2% of monthly minimum wage earnings; in the UK, 4.5%; in the US, 10%; in South Africa, 12%; in Brazil, 17%; and in Indonesia, 18%. In Ghana, it is exceptionally high at 107% of the monthly minimum wage.

Nigeria’s case is the most extreme: with a minimum wage of ₦70,000 and a passport fee of ₦100,000, the ratio reaches an astonishing 143%, placing the country at the very bottom of the global affordability scale.

According to him, this trend reveals a clear divide: countries that treat passport issuance as a public service keep costs low, while those—like Nigeria and Ghana—that adopt neoliberal approaches commercialise the service to the detriment of citizens.

To Nigerians grappling with the new cost, Dr Oni urged careful planning to avoid falling prey to extortion. “Corruption in Nigeria’s passport application process is rampant.

Despite official anti-corruption rhetoric, the passport and driver’s licence systems remain among the most corrupt in the country. If you are in a hurry, officials exploit that urgency, often forcing applicants to pay many times over the official fee,” he warned.

Dr Oni expressed doubt over government promises of subsidies or waivers, pointing out that such schemes are frequently poorly designed, badly executed, and prone to abuse. He concluded that since passports are only relevant to a segment of the population, the government is unlikely to prioritise relief measures.

“You’d be surprised how many Nigerians don’t even know what the Nigerian passport looks like, let alone feel concerned about a price hike. This limited awareness means there’s little public pressure on the government to reconsider the decision and they know it,” he noted.