By Jeremiah Aminu

Throughout the course of history, Africa has witnessed the emergence of different governmental systems in the course of its political evolution. In the pre-colonial era, for instance, monarchy (both constitutional and absolute) served as the dominant system of governance whereby a king, queen, or emperor directed the political operations of different empires.

Following the partial displacement of this system of government by colonial rule in the 19th and 20th centuries, Africa witnessed the advent of a centralised and unitary governmental system in which political power and authority were highly concentrated in the hands of the colonial government with little or no inclusion of Africans in matters of governance.

Upon independence, this form of governance subsequently resulted in the adoption of a parliamentary system of government in many African countries (most especially those formerly colonised by the British such as Nigeria and Ghana) with a Governor-General as the head of state representing the Queen of England and a native Prime Minister serving as the head of government and administration in these African countries.

READ ALSO: WHO urges African governments to prioritise eye health as vision crisis deepens

However, due to the rife political corruption, strife, and crises that dominated this system of governance, the military in many African countries seized power to usher in the era of military rule which was characterised by a centralisation of power in the hands of the Head of State with the authority to enforce “decrees” as laws.

This form of governance dominated the political system of many African countries in the 20th century (some of which include Nigeria, Togo, Ghana, and Egypt).

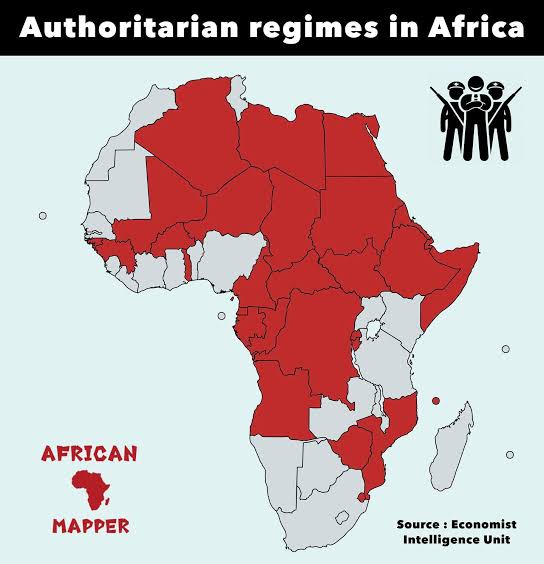

Since the displacement of military rule, many African countries have adopted democracy as a predominant mode of governance in the 21st century. However, despite the benefits that this governmental system offers such as equal participation in governance, freedom, and liberty, many African leaders utilise it as a mask to perpetuate authoritarianism (which is characterised by the centralisation of political power in the hands of the ruling government).

An instance of this can be seen in the case of Uganda’s President, Yoweri Museveni, who has been constantly faced with allegations of manipulating state institutions to induce fear, eliminate the political opposition on trumped-up charges, and oppress the Ugandan citizens through military tribunals despite a ban by the Supreme Court. This is corroborated by a Guardian report (2025) by Carlos Mureithi where he stated that:

“Ugandan opposition politicians have accused the president, Yoweri Museveni, of attempting to quash dissent by prosecuting opponents on politically motivated charges in military courts in the run-up to presidential and legislative elections next year. The government is pushing to introduce a law to allow military tribunals to try civilians despite a Supreme Court ban on the practice. In November, the opposition politician, Kizza Besigye, was detained in Nairobi, Kenya, alongside his aide, Obeid Lutale, and taken to Kampala where they were charged before a military tribunal with offences including illegal possession of firearms, threatening national security, and later treachery”.

Similarly, the former president of Tanzania, John Magufuli, also faced accusations regarding his authoritarian regime as president which lasted for six years until his demise in 2021. This is documented in a 2019 report by Amnesty International that exposed how Magufuli manipulated political power to oppress the opposition, human rights activists, and journalists, as well as repress the media:

“Since President John Magufuli took office in November 2015, the government of Tanzania has applied a raft of repressive laws restricting the rights of opposition politicians, human rights defenders, activists, researchers, journalists, bloggers and other online users. Cumulatively, the application of these laws has had a chilling effect on the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly”.

This now raises an important question: Why is authoritarianism still prevalent in 21st-century Africa despite the predominance of democracy in the political constructs of many African countries?

The first reason can be traced to the postcoloniality of Africa. This is apparent in the governmental system of postcolonial Africa which functions as an inherited reproduction of the same system of violence, power monopolisation, and power domination that characterised colonialism. Therefore, there is always a high tendency for the political hegemony (the ruling party) to monopolise and manipulate their political power and authority to oppress the masses and eliminate the opposition even in democratic regimes.

Another notable factor is the manipulation of power by the members of the executive (such as the president). It is as a result of this that they disregard the orders of the judiciary and even enforce laws through the legislative arm to preserve their interests and retain political power. As an instance, one can reference the event in which the Ugandan parliament initiated a constitutional amendment concerning the 75-year age limit for presidency so that Museveni could run for another term in 2021. This, hence, demonstrates how the predominant power of the executive poses a problem to the checks and balances that characterise separation of power in democratic regimes, since they continue to manipulate the other arms of government to bend to their will.

READ ALSO: Super Eagles intensify training in South Africa ahead of World Cup qualifier

On a conclusive note, the entrenched nature of authoritarianism within the democratic regimes in Africa now puts forward these final questions: Can authoritarianism be totally filtered out from Africa’s political terrain? Or will democracy continue to act as a veil to ensure its covert operations within many African countries?