By Sakariyah, Ridwanullah

For decades, a ringing telephone in Nigeria was a rare sound, usually associated with power, privilege, or official authority rather than everyday life.

From colonial offices in Lagos to the frustration of waiting years for a dial tone, access to communication reflected who mattered and who did not.

But today, as millions of people scroll, stream, and speak across mobile networks, the story of Nigeria’s telephone system reveals how a once-exclusionary technology was transformed into a national lifeline. Thus, this report traces the historical emergence of telephony in Nigeria from the colonial era till the present time.

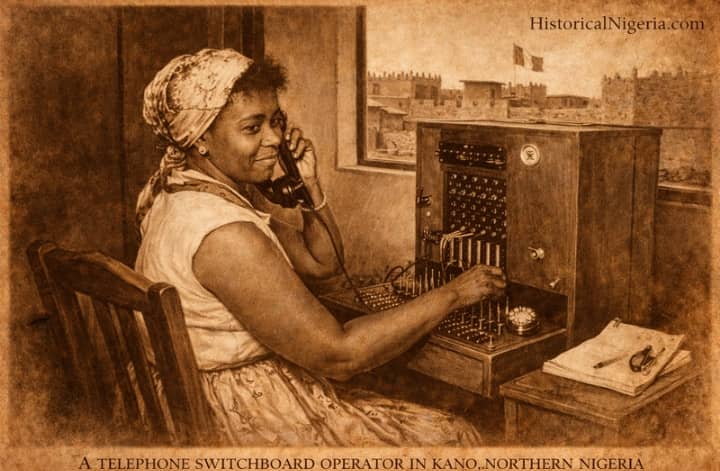

Nigeria’s encounter with the telephone system can be traced back to 1886, when the British colonial administration installed the first telephone line in Lagos to connect government offices and commercial outposts.

Historical records cited by the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC) and documented in colonial archives referenced by THISDAY and The Guardian Nigeria show that early telephone services were strictly administrative, when they served colonial officials and European trading firms rather than the indigenous population.

During the twentieth century, telephone services were managed by the Post and Telecommunications Department (P&T).

According to a historical overview published by the NCC in its Telecoms Industry Review, access to fixed telephone lines remained limited, highly bureaucratic and urban-centred.

By Nigeria’s independence in 1960, teledensity stood at less than one line per 1,000 people, with most connections located in Lagos, Ibadan and a handful of regional capitals.

In 1985, the Federal Government merged the telecommunications arm of P&T with Nigerian External Telecommunications to form Nigerian Telecommunications Limited (NITEL). Official government gazettes and retrospective reporting by The Punch and BusinessDay describe the move as an attempt to consolidate domestic and international telecom operations under a single national carrier.

However, the experiment proved largely unsuccessful. By the late 1990s, NITEL struggled with antiquated infrastructure, poor maintenance and chronic underinvestment. According to NCC data cited by Reuters and The Guardian Nigeria, Nigeria had fewer than 500,000 connected fixed lines by 1999, which served a population estimated at over 100 million. Later on, waiting periods for landlines stretched into years, and fault repairs were often delayed indefinitely.

At some point, telephones became more than what a common person could afford. In fact, the expression “telephone is not for the poor” was long used to symbolise the elitist era of the NITEL monopoly which is often described as a popular myth, yet it stems from a documented 1989 press report.

During a 1989 visit to Akure, then-Minister of Communications Colonel David Mark responded to concerns about the mass disconnection of NITEL debtors.

He reportedly stated that individuals could not justify non-payment by claiming poverty, adding that, at the time, “poor people… did not own telephones”. The following day, Nigerian newspapers distilled this sentiment into the now-infamous banner headline: “Telephone is not for the poor”.

While David Mark has consistently denied using that exact phrasing verbatim, contending that his remarks were “twisted” or taken out of context, the phrase is more than a retrospective metaphor. It is a verified media artifact of the late 1980s that captured the restrictive reality of telecommunications in Nigeria prior to deregulation.

What is more, repeated attempts to privatise NITEL failed. According to reporting by Reuters and BusinessDay, the company accumulated massive debt, lost subscribers to illegal private exchanges and mobile alternatives, and eventually ceased meaningful operations. NITEL was formally liquidated after the collapse of multiple privatisation efforts.

Subsequently, Nigeria’s telecommunications landscape changed decisively in January 2001 with the auction of Digital Mobile Licences (DMLs). The process, overseen by the NCC, was widely reported by BBC News, Reuters and Nigerian dailies as one of the most transparent privatisation exercises of the era. Also, MTN Nigeria and Econet Wireless, alongside the state-owned M-Tel, emerged as winners, generating approximately $285 million in licence fees for the government, according to NCC records.

Then mobile telephony expanded rapidly. NCC statistics as cited by The Economist and Afrobarometer show that Nigeria’s teledensity rose from below 1 per cent in 2001 to over 40 per cent by 2011. Mobile phones transformed commerce, journalism and everyday social interaction. Afrobarometer surveys consistently link mobile phone ownership in Nigeria to improved access to markets, information, and civic participation.

By the 2010s, the sector had shifted focus from voice services to data and broadband connectivity. Submarine cables such as SAT-3, MainOne, and Glo-1, documented by Reuters and BusinessDay, expanded Nigeria’s international bandwidth capacity. Fibre-optic deployment increased within major cities, though expansion was slowed by high right-of-way charges, infrastructure vandalism and unreliable power supply.

Later on, Nigeria entered the 5G era between 2021 and 2022, following spectrum auctions reported by the NCC and covered extensively by Reuters, Bloomberg and The Guardian Nigeria. While 5G services are currently limited to select urban areas, NCC figures indicate that Nigeria now has over 200 million active mobile subscriptions, though broadband penetration remains uneven.

From the foregoing, it can be understood that Nigeria’s telephone system reflects a broader story of inequality, reform, and technological leapfrogging.

The collapse of fixed-line infrastructure gave way to a mobile-first revolution. Today, the challenge is no longer access alone, but the affordability, quality, and resilience of digital connectivity in an economy that’s increasingly dependent on data-driven communication.

For More Details, Visit New Daily Prime at www.newdailyprime.news