By Sakariyah, Ridwanullah

In the buzzing professional world in Nigerian cities, the 21st-century Nigerian woman faces a choice: what name will she answer to after marriage? Many professionals are now using a hyphenated surname to keep the professional reputation they built, with a view to preserving their “brand” while acknowledging their new family. Yet, this modern approach stands alongside the traditional path where women fully adopt their husband’s surname, which often leads to unexpected career roadblocks. This tension between preserving a career identity and honouring cultural expectations defines a complex cultural conversation in Nigeria today.

This choice, whether to change, hyphenate, or keep one’s name, is never simple; it affects a woman’s career path, her sense of self, and the memory she leaves behind for her children. For professionals, the surname change is often a costly exercise in rebranding. In competitive fields like media, tech, and law, where reputation is key, a new name can confuse clients and disrupt established networks. A 2024 NOIPolls study, looking at professionals, suggested that about 15% of women felt a hidden bias or negative impact on their career growth after changing their names.

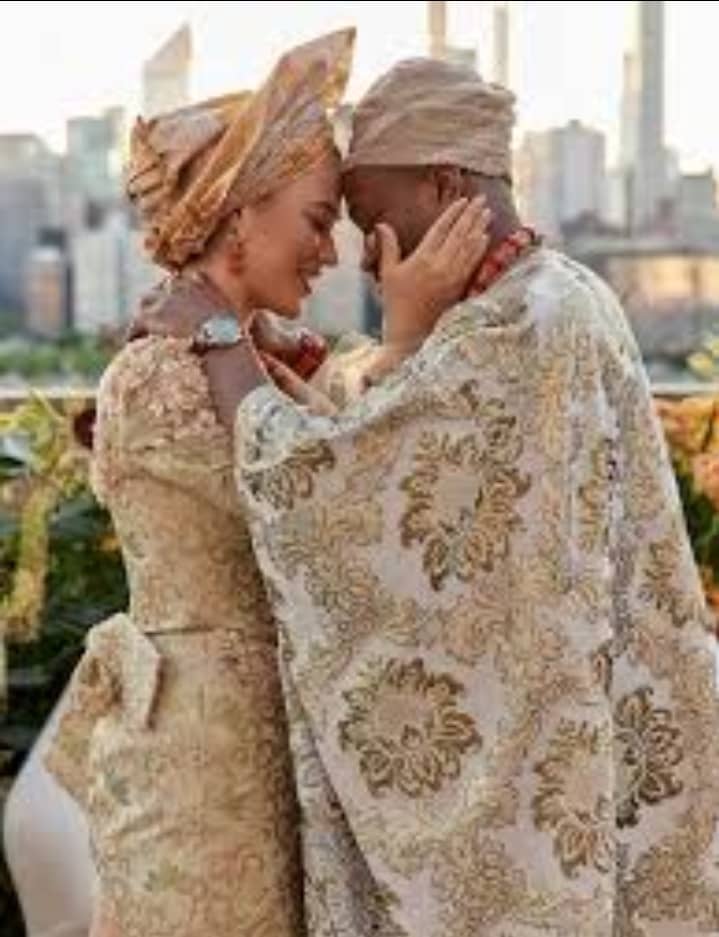

READ ALSO: DJ Cuppy opens up on post-wedding blues after Temi’s lavish ceremony

The law complicates things further. Although the Marriage Act doesn’t actually force a woman to change her name, the systems put in place by government bodies like the Nigeria Immigration Service (NIS) and others create huge hurdles.

Women who change their names must navigate tedious and expensive processes involving legal papers and newspaper announcements to update everything from professional licenses to passports. This administrative difficulty often makes women feel pressured to conform. The choice by celebrities like musician Tiwa Savage and novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to keep their professional names continues to fuel social media debates, showing the deep-seated pressure women face to follow tradition.

Beyond career implications, the surname holds deep emotional meaning. Nigeria’s major cultures (Igbo, Yoruba, and Hausa) trace family history through the father’s side. When a woman gives up her maiden name, she is symbolically cutting ties with her birth family’s history. Speaking in an interview with TVC, Mrs Abdullah explains that for many women, the name change can bring a subtle feeling of loss of heritage, like erasing the first part of their life story, and that “even the religion of Islam doesn’t permit change of surname post-marriage. However, for others, the new name is happily taken as a sign of commitment to their new family. The 2023 Nigerian Institute of Social and Economic Research report on gender roles confirms that choosing to keep one’s name is becoming more popular, with name retention rates among younger women rising by an estimated 10% since 2020.

The long-term impact is one of legacy. When a woman fully adopts her husband’s name, her children naturally carry that same name, continuing the male family line while often making her own family name fade from memory. Feminist critics argue this practice contributes to the erasure of women’s history in the public eye. The legal framework supports this critique: Legal practitioner Christiana Longe has noted, “No law in Nigeria mandates a woman to change her name due to marriage. It is more of a societal and cultural practice than a legal obligation.”

READ ALSO: Meet Shawn Faqua, Sharon Maduekwe who made history with Nigeria’s first train wedding

Furthermore, anthropologists like Dr. Ifi Amadiume, whose work on African gender systems is foundational, point out that this is largely due to the colonial legacy of the 1914 Marriage Ordinance, which brought a strictly patriarchal naming system that overshadowed local traditions where women sometimes held greater lineage power. This has led legal advocates to push for reforms in the National Assembly that would clearly state a woman’s right to choose, and remove the administrative roadblocks for those who want to keep their names.

Looking at other countries shows different ways forward. Spain’s dual-surname system and Iceland’s patronymic system prove that strong family structures don’t require the mother’s maiden name to be completely dropped. Within Nigeria, the rise of digital identities and the growing financial freedom women have through movements like #SheMeansBusiness, #SheLeadsAfrica, and the like are making it easier to manage the change. The focus must shift to policy and awareness campaigns that educate women on their legal rights. Only when the decision to keep a name is met with the same ease and respect as the decision to change it can Nigerian women truly step into their full potential, free to choose the name that best reflects their identity and career.