Following incessant building collapse in Nigeria’s commercial headquarters, Lagos state, fingers are pointing at poor regulation, substandard materials, and unqualified builders as major factors.

It would be recalled that on 27 October, 2025, the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) confirmed the collapse of a two-storey building at 49 Coates Street, by Cemetery, off Oyingbo Road in Lagos State.

The agency disclosed that 13 persons were rescued from beneath the rubble and received medical attention at the Federal Medical Centre (FMC), Ebute Metta, with no casualty recorded.

However, on 30 October, tragedy struck again as the Lagos State Emergency Management Agency (LASEMA) announced the death of one person following the collapse of a three-storey building at No. 28, Baale Alayabiagba Street, Ajegunle, Apapa area of Lagos.

Eight victims were rescued alive, while the cause of the incidents were yet to be ascertained.

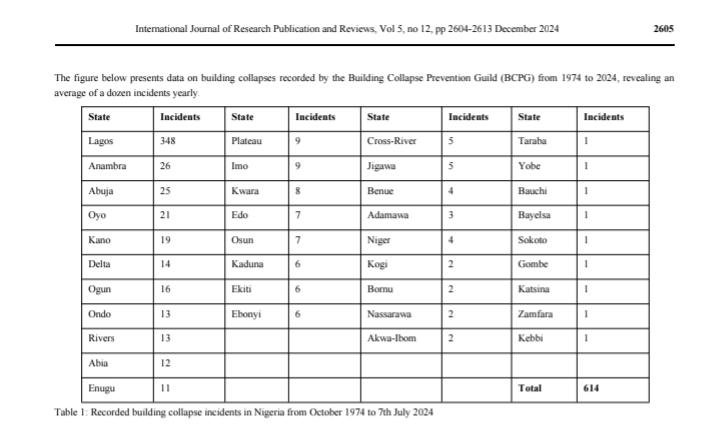

According to data from the Building Collapse Prevention Guild (BCPG), Nigeria has recorded over 678 building collapses, claiming more than 1,639 lives.

A 2024 report published in the International Journal of Research Publication and Review further revealed that out of 614 documented cases of building collapse between 1974 and 2024, Lagos state alone accounted for about 348, representing over half of all incidents nationwide.

The tragedy of quackery

In an exclusive interview with New Daily Prime on the effects of substandard building licensing procedures, and accountability, the National Publicity Secretary of Nigerian Institute of Building (NIOB), Usenobong Atangaedi, with 15-year experience, noted that these recurring tragedies are not accidents but consequences of neglect and weak enforcement.

Read Also: Two-storey building collapses in Lagos, many died

Speaking on the growing concern with our correspondent, Atangaedi described the recurring tragedies that have claimed several innocent lives and destroyed properties worth millions of naira as “preventable” if only the right professionals were engaged and the Nigerian National Building Code (NNBC) was properly enforced.

“If the right things were done from the beginning, the way in which buildings collapse will not be as we have been witnessing in our country,” he said, adding that, “most of the structures that fail in Lagos were either distressed or poorly supervised. Unfortunately, people choose to engage in those that you can safely call quacks.”

He noted that while many of the affected structures in Nigeria, especially Lagos had long exceeded their design lifespans, they remained occupied without proper evaluation or controlled demolition by relevant authorities.

According to him, the NNBC clearly outlined standards for supervision and construction, but implementation remains poor across most states.

“And when we are talking about the NNBC, has been succinctly stated, especially in section 15, sub section 12 that the supervision of building construction in Nigeria must be taken care of by registered builders who are trained in building production management, material strength, all aspects of assembling building, and making it become a unit. That is not happening in so many ways in our country,” he added.

Weak compliance and political interference

On compliance with safety standards, Atangeadi said the failure begins at the policy level, as most state governments have yet to domesticate or legislate the National Building Code, which would empower regulatory agencies to enforce it.“

There must be that political will by the political class to make sure that this is enshrined in all aspects of our building infrastructural development.

“At the level of the federal government, especially at the federal capital territory, Abuja, recognition has been given to the National Building Code. Some states are also recognizing it and have taken serious steps to make sure that they recognize the National Building Code and involve professionals,” he said.

He further criticised the current system of monitoring construction projects, noting that many of those assigned to enforce building standards lack technical knowledge.

“Affiliated people are enlisted to go around the construction site, but they will go and start harassing people, not only to ensure compliance, most of the time they are to make money for themselves and the people that engage them,” he stated.

Socio-economic consequences of building collapse

Speaking on the social and economic impact of building collapses, Atangaedi described the effects as devastating, both for victims’ families and the broader society.

“The members of the immediate family of the bereaved are going to be traumatised in the sense that their loved ones lost their lives in things that they may not be directly contributory to reach, you know.

“So, that trauma will always be there. And it also will affect their psychological well-being, their mental well-being,” Atangeadi said.

He condemned the government’s “fire-brigade” approach to such incidents, stressing that condolences and emergency responses are not enough without preventive measures.

Substandard materials and quackery

The NIOB spokesperson also identified substandard construction materials as a major contributor to structural failures. He cited poor-quality reinforcement bars and wood as major problems in the market.

“If you buy a 12mm iron rod today, you might end up giving a 10mm rod,” he warned. “These are going on even in a situation whereby we have a standard organisation of Nigeria, which ordinarily, on the surface, it is expected that they also check these substandard materials in the market. We also have NIAs.”

Atangaedi, who is a registered builder with the Council of Registered Builders of Nigeria (CORBON) further questioned how such materials gain entry into Nigeria, calling for stronger import oversight and market regulation.

Call for collaboration and professional inclusion

With over 15 years of experience, Atangeli emphasised that long-term solutions must centre on collaboration among government agencies, professional bodies, and the private sector.

“The collaboration between the governments—state, federal—and professional bodies is long overdue,” he said.

“There must be a calculated and conscious synergy between the government and professional bodies, and private developers. Each has a critical role to play.”

He revealed that professional bodies like the NIOB have often attempted to partner with state governments to strengthen compliance monitoring but faced bureaucratic bottlenecks.

“We once approached a state government through the Commissioner of Urban Planning and Physical Development and requested that we synergize.

“We bring in our members to be involved in checks and balances, in enforcing compliance to approve building plans. Much was not really gotten out of it.

“It did not yield much of the expected result because of one or two bottlenecks in the way our management runs. This does not mean that we cannot work . The time to activate the collaboration is now,” he said.

According to him, private developers and estate firms also have a role to play by ensuring that certified professionals handle every stage of construction, from design to supervision.

The way forward

Atangaedi concluded by urging all stakeholders to act decisively to prevent further loss of lives.

“The best time to act was yesterday,” he stressed. “The second-best time is now. The government must take the lead, professionals must uphold ethics, and citizens must stop cutting corners. It is cheaper to hire quacks, but the cost of their mistakes is often paid in human lives.”