In Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, a silent war is being waged—not just against cancer, but also against the soaring costs and systemic challenges that threaten the lives of those battling the disease.

In 2020, Nigeria recorded 124,815 new cancer cases, with 51,398 in males and 73,417 in females. By 2022, the country recorded an average of 127,000 new cases and 79,000 cancer-related deaths. Breast cancer represents 27% of all cases, while cervical cancer accounts for 14%, liver cancer for 12%, prostate cancer for 12%, and colorectal cancer for 4.1%.

According to the National Cancer Institute (NIH) recent data in 2024, cancer incidence increases with age. It rises from fewer than 25 cases per 100,000 people under 20 years old to about 350 per 100,000 at ages 45–49, exceeding 1,000 per 100,000 for those aged 60 and above; cancer is no longer an isolated affliction—it’s a national crisis.

“Many people feel it’s a death sentence,” said Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, who shared his own cancer survival story in 2014. However, he emphasised that, “Cancer is not a death sentence; it is a labour of willpower. Some hard labour is involved, but ultimately, you can be victorious.”

The Human Cost of Delay

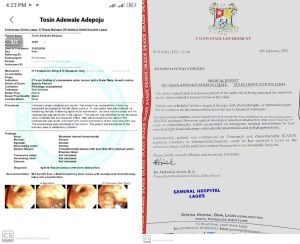

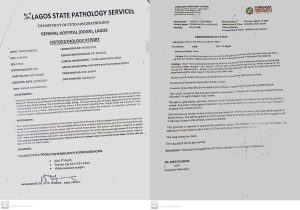

After speaking with Adepoju Adewale, a 30-year-old Lagos resident, it became clear how deeply personal Nigeria’s cancer crisis can become. Following a routine hospital visit in March 2024, Adewale was diagnosed with stage 4 colon cancer. He faced not only a physical battle but also a financial one—marked by a cascade of costs: ₦214,000 ($142) for an initial colonoscopy and biopsy, ₦1.2 million ($800) for surgery, and ₦3 million ($2,000) for six months of targeted therapy.

“How will I do this?” he asked, eyes hollow with worry. “Every round of chemotherapy came with blood transfusions. I became anaemic. At one point, I couldn’t keep going.” stated by him.

Three sessions of chemotherapy left him vomiting for days. A resulting intestinal obstruction meant even more time in the hospital. Eventually, Adewale paused treatment, relying on self-medication as the financial strain became overwhelming

When Treatment Is a Privilege

Nigeria’s public healthcare system remains woefully under-resourced. Patients like Adewale are often referred to private hospitals with limited transparency and skyrocketing costs. Across the country, hospitals lack functioning diagnostic equipment, radiotherapy machines, and trained oncologists.

“We’re moving from one facility to another just to get basic tests. It’s draining—financially, emotionally, physically,” Adewale said.

Psychological Impact of Cancer

Like Adewale, many cancer patients experience stress and anxiety as a direct result of their diagnosis and treatment. Over 78% of cancer patients in Nigeria report experiencing psychological distress. This, paired with the social stigma surrounding cancer, has left patients isolated and unsupported. “People can’t relate. They just judge online. I didn’t even make any videos,” Adewale said, referring to the social media backlash he received. “Ranting won’t change anything.”

A National Pattern of Suffering

Adewale’s story is not unique. Across TikTok and Instagram, young Nigerians are sharing heart-wrenching accounts of losing parents and siblings to cancer.

A TikTok user identified as Tshine has sparked widespread conversation after revealing that her mother is battling skin cancer. In her post, she questioned the government’s payment structure, highlighting the stark contrast between the national minimum wage and the exorbitant cost of chemotherapy. “₦5 million for chemotherapy. How much is minimum wage?” she asked, referring to her mother’s struggle with skin cancer after 50 years of outdoor labour.

Another user, Omotola, wrote: “We spent our last kobo trying to save her,” mourning her mother, who died of colon cancer in 2023. With Nigeria’s minimum wage at just ₦70,000 per month, the cost of a single chemotherapy cycle can exceed a full year’s income—making life-saving treatment unaffordable for many.

A Government Trying to Respond

In 2024, the Nigerian government announced a ₦37.4 billion oncology initiative to develop six cancer centres across the country. The centres, set to be constructed in teaching hospitals in Lagos, Benin, Jos, Nsukka, Katsina, and Zaria, aim to decentralize treatment and increase accessibility.

“This is a step in the right direction,” says Dr. Femi Adeyemi, a clinical oncologist in Abuja. “But without subsidized treatment or universal healthcare, many will still die simply because they cannot pay.”

Nigeria currently lacks a comprehensive national health insurance system capable of absorbing the burden of long-term cancer care. Patients often rely on crowdfunding or international donors to stay alive.

What Lies Ahead

Cancer remains the second leading cause of death globally, and in Nigeria, its rise is compounded by poor regulation, economic hardship, and cultural taboos. While breast, cervical, prostate, and liver cancers dominate the charts, colorectal cancer—the type affecting Adewale—is silently gaining ground, particularly among young adults.

“If nothing changes, cancer will overwhelm us,” Adewale warns. “It already is.”

His plea—like those of thousands of others—is not just for survival, but for a system that doesn’t force people to choose between life and bankruptcy.