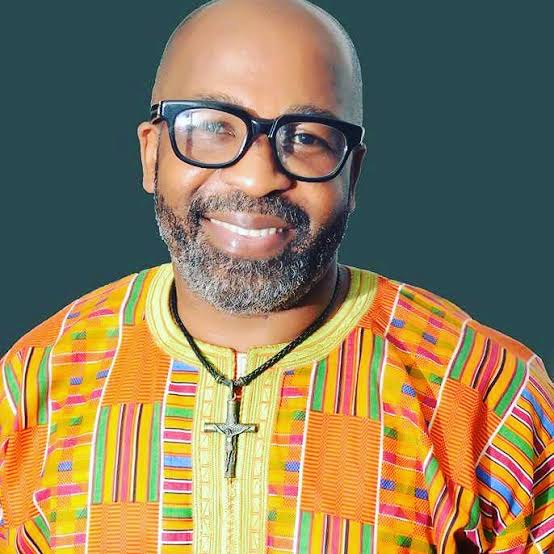

Veteran Nollywood actor Yemi Solade has spoken candidly about his fallout with a former church and its leadership over what he described as unrealistic religious demands that nearly jeopardised his career.

Speaking on a recent episode of the Honest Bunch podcast, the 64-year-old actor recounted a pivotal 2013 incident that led to his complete withdrawal from church attendance, after a pastor asked him to stop accepting film roles that required him to work on Sundays.

“I’d been told in the church that I should tell producers not to call me for work on Sundays. And I cursed the pastor,” Solade said, recalling the confrontation.

The actor condemned the directive, stating that it was an intrusion into his source of livelihood, especially in an industry that often requires weekend shoots and tight filming schedules.

“It is from that thing that you said I shouldn’t do on Sunday that I put hand in my pocket and I drop here.

So when will I have time to work?” he asked.

READ ALSO: Yemi Solade rejects award, organizers withdraw

Solade questioned the biblical basis for such demands, arguing that Sunday, as designated in the Greco-Roman calendar, is not a universal mandate for Christian worship.

“There’s no way in the Bible that Sunday… is set aside for people to go and assemble and shout God and Jesus.

And you’re telling me not to leave my house and go to where my chop is. You want to ruin my career?” he said bluntly.

Since his exit from regular church life, Solade says he has found greater inner peace, countering the common belief that religious attendance is a prerequisite for spiritual fulfilment.

“The notion that if you don’t attend church, you will die… probably I’ve not seen anything change. Rather, I have peace. I do well,” he shared.

He claimed that his church days were filled with constant “messages or sort of disturbances” and that detaching from organised religion had actually improved his quality of life.

Solade also criticised financial sacrifices made in the name of religion, narrating a personal encounter with an elderly technician who diverted part of his payment to church offerings.

“Do you know that you took my money to that church? You gave part of it. That blessing is mine now,” he joked.

“If the prayer there is efficacious, it will come to me.”

He described such actions as misguided priorities, where people neglect their professional responsibilities in favour of maintaining church appearances, often at the expense of their clients or employers.

Turning to the history of Nollywood, Solade challenged the widely accepted narrative that Nigeria’s film industry began with the 1992 Igbo-language hit, Living in Bondage.

“The first movie that you call home video was actually produced by a man who is still alive, Ade Ajiboye, we call him Big Abbas.

Shosho Meji, as produced by Ade Ajiboye, was around 1988,” he said.

He also cited television dramas such as Things Fall Apart as evidence that structured Nigerian storytelling had existed on screen well before Living in Bondage gained prominence.

“Things Fall Apart was on television in the mid-80s. So, this notion that Nollywood started in ’92 is misleading,” he stated.

Solade further claimed that, historically, the South-East was slow to institutionalise theatre education, unlike other regions of the country. Drawing on his academic background from Obafemi Awolowo University, he referenced the Nigerian University Theatres Festival (NUTAF), which, he said, had no Eastern representation at the time.

“When I was a student in Ife, only six universities participated in NUTAF, and none existed in the East,” he asserted.

While acknowledging the South-East’s later contributions to Nollywood, Solade criticised what he described as the oversimplification of the industry’s origins, calling for greater recognition of earlier contributions from the South-West and North.