Kurdish-led forces in Syria have announced their withdrawal from a major detention camp in the country’s north-east that houses tens of thousands of people linked to Islamic State, as Syrian government forces continue a rapid advance across the region.

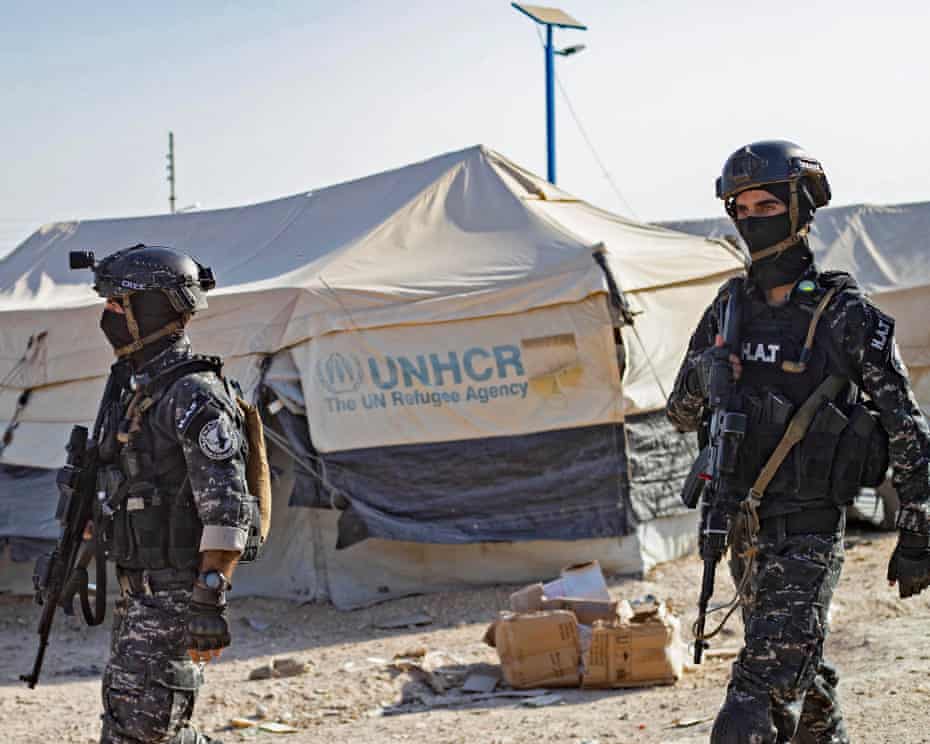

The future of al-Hawl camp has become a major concern for neighbouring states and the wider international community. The camp holds families of suspected IS fighters, including some of the group’s most hardline foreign women, and has long been described by security officials as a breeding ground for extremism.

A smaller number of female detainees, including Shamima Begum, are held at al-Roj camp further north-east, which remains under Kurdish control.

The Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) said the withdrawal from al-Hawl was forced by deteriorating security conditions.

“Our forces were compelled to withdraw from al-Hawl camp and redeploy near cities in northern Syria facing increasing risks and threats,” an SDF spokesperson said, describing the move as a failure of the international community.

The Syrian government said it would assume responsibility for the camp, accusing the SDF of abandoning it without adequate guards and allowing detainees to escape. It made similar claims about a prison in Raqqa, where it said 120 prisoners had fled. The SDF denied those accusations.

The withdrawal came as government forces made sweeping gains across north-east Syria, taking advantage of the rapid collapse of SDF control in several areas. Raqqa and Deir el-Zour fell on Sunday after tribal groups defected from the Kurdish-led force, prompting a retreat from Arab-majority regions.

The speed of Damascus’s advance has been striking. Until days ago, the SDF controlled nearly a third of Syria with backing from the United States. The shift marks the biggest change in frontlines since the fall of former president Bashar al-Assad in December 2024.

A 14-point ceasefire agreement signed on Sunday by Syria’s president, Ahmad al-Sharaa, and the SDF commander, Mazloum Abdi, collapsed within a day after a tense meeting in Damascus.

On Tuesday night, the Syrian presidency announced a fresh four-day ceasefire aimed at reviving the agreement. It said Kurdish-majority cities such as al-Hasakah and Qamishli could remain under Kurdish administration, with local residents forming security forces.

The statement also said Abdi would nominate candidates for deputy defence minister, parliamentary seats and public sector roles.

The announcement appeared to ease immediate fears of further fighting and offered reassurance to Kurdish officials that their rights would be protected.

Earlier, Syrian officials accused Abdi of delaying the handover of Kurdish-led institutions to Damascus. Ilham Ahmed, a senior Kurdish official, said Abdi had asked for a five-day grace period, which was initially rejected.

“They wanted everything handed over immediately,” she said. “With or without the meeting, they wanted war.”

Following the failed talks, Kurdish leaders called for mass mobilisation in Kurdish-majority areas. SDF-affiliated media published images of civilians holding rifles in preparation for further clashes.

Fighting continued on Tuesday, with shelling reported in Kobani near the Turkish border and government forces entering parts of al-Hasakah.

So far, Damascus’s gains have been concentrated in Arab-majority areas where resentment towards the SDF had been growing. Kurdish forces have pulled back towards areas closer to the Iraqi and Turkish borders, which are predominantly Kurdish.

Analysts warn that if government forces move into Kurdish-majority regions, the fighting could become far more intense. The SDF has entrenched positions there, including heavy weapons, drones and tunnel networks.

Many Kurds view the conflict as existential, pointing to mass killings carried out by government forces last year in Sweida province and along the Syrian coast as a warning of what could follow.

The Syrian government said it would not enter Kurdish areas, insisting its objective was to restore stability and protect state institutions.

The SDF was the United States’ main partner in Syria during the fight against Islamic State and played a central role in defeating the group’s so-called caliphate in 2019. It is the military arm of a Kurdish autonomous administration that developed its own governing structures and protected Kurdish rights long suppressed under the Assad family.

After Assad’s fall, negotiations began over the future of that autonomy. While an agreement was signed in March to integrate the SDF into Syria’s army, tensions persisted and clashes continued.

At the weekend, the US urged Syrian forces to halt their advance at the Euphrates River, but Damascus pressed on. Washington has since remained largely silent.

The government’s offensive has allowed it to regain control of most of the country, including key oil and gas fields and major dams.

US policy appears to have shifted towards Damascus over the past year. The US envoy to Syria, Tom Barrack, said the SDF should fully integrate into the Syrian state, describing the moment as an opportunity for Syrian Kurds.

He said the SDF’s original role as the main force against Islamic State had largely ended, as Damascus was now prepared to take control of security duties, including detention facilities and camps.