By Jeremiah Aminu

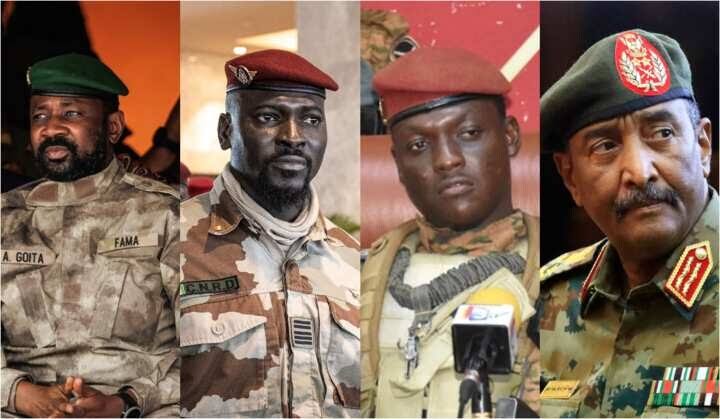

Since 2020, there has been a surge of military coups across Africa in an attempt to install military Heads of States and displace corrupt political leaders in democratic regimes who practice “democrazy” (government against the people) rather than “democracy” (government for the people). So far, there have been nine successful coup attempts associated with a variety of reasons for their initiation. Insecurity, for instance, serves as one of the factors for the recent coup wave. In this regard, one can reference the 2022 coup in Burkina Faso which engendered the reign of Ibrahim Traoré due to the inability of the prior government to combat the alarming insecurity, caused by Islamic insurgency, which left thousands dead and millions displaced within the country. Similarly, in Mali, Colonel Assimi Goïta attributed his initiation of the 2020 coup to insurgency and political corruption.

Furthermore, the initiation of some coups has been linked to the protection of democracy. The 2021 coup in Guinea which resulted in the succession of Conde’s administration is an example which was led by Colonel Mamady Doumbouya to curtail Conde’s mismanagement of political power and authority to extend his tenure in office. In Gabon, the military displaced Ali Bongo’s administration shortly after the announcement of his victory in the election which was said to have been subjected to electoral and political misconducts. As stated in an article by Alex Vines, “the new junta called it a ‘Freedom Coup,’ ending the fifty-six-year-long rule of the Bongo family”. Relatedly, a similar coup in 2023 (although unsuccessful) that hinged upon electoral and political misconduct also surfaced in Sierra Leone.

READ ALSO: NASS leaders seek urgent reforms to strengthen democracy, security

With the rising trend of military coups in Africa and the steady decline of democratic rule within the continent, the question concerning the declining state of democracy within the African political space has dominated discussions on African politics. While some of the masses have viewed the military governmental system as a solution to the political excesses of the “so-called democratic regime” of corrupt African political leaders, many have stated their suspicions regarding this recent coup wave within the continent.

Alex Vines (the Director of Chatham House), for example, in his article, “Understanding African Coups”, revealed his suspicions concerning the recent military coup trend through what he termed as the “putschist playbook”. This “playbook” is employed by the military for a foremost objective—to retain political power as long as possible. Central to this strategy is seeking popular support from the masses in order to justify their reason for the initation of the coup and retain political power and authority for a long period. Vines, in his article, stated that:

“Popular support—or at least the appearance of it—is crucial to this strategy. Some coups attract popular support because they navigate blocked political successions like in Gabon and Guinea, where voters lost faith in the political system and consequently supported a military coup. Putschists were able to claim popular concerns over accountability and length of tenure as justifications. In other places, notably Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, they have encouraged anti-colonial and anti-French sentiment among the youth to sustain grassroots approval. External actors such as Russia have also encouraged anti-western sentiments and appear to offer praetorian guard services to protect these juntas from counter-coups”.

The recent military administrations have also proven difficult to reason with as regards the transition of power to civilian rule due to their recurrent extensions. In this respect, Vines referenced how the military leaders in Burkina Faso and Mali renegotiate discussions concerning the transition of power to civilian rule in order to extend their tenure in office:

“Burkina Faso and Mali are supposed to hold elections in 2024, but Mali’s ruling junta issued a decree on April 10 suspending all political activities until further notice citing a need to preserve public order”.

Traoré, on the other hand, extended his rule by five years in Burkina Faso with reference to the need to prioritise and enhance the national security of the country. Similar extensions of the transition of power to civilians have also been seen in Gabon, Chad, and Guinea. Thus, the strategy is overt: initiate a coup, seize power, promise a transition of power, and constantly extend its duration.

It is amidst this political crisis that experts have shared their views concerning the declining degree of democracy within the African political space due to the rising military coup trend coursing across the continent, most especially in West and Central Africa. Ahmed Idris, a reporter at Al Jazeera, shared his viewpoint concerning this issue where he remarked that:

“Political analysts believe that it’s a trend that’s emerging in Africa… [and] unless leaders in Africa sit up and listen to the people, certainly we will have an epidemic on our hands,” he said.

Sanusha Naidu, a senior research fellow at the South African think tank The Institute for Global Dialogue, also commented on this trend where she stated that:

“It is a reaction not just to a broken system, and an undemocratic one. It’s also the fact that the democratic process in itself is raising a lot of contradictions in terms of people feeling as if they can’t trust the political process, the democratic process, and are basically looking towards the military as possibly being that institution that can actually turn things around,” she commented.

READ ALSO: Independence Day: Adeleke calls for rule of law to strengthen Nigeria’s democracy

In all that has been said so far, the foregoing serves as a clarion call to African democratic leaders to forego their system of “democrazy” and institutionalise “true democracy” itself which places the people’s priorities and interests at the core. If this trend of political corruption, government oppression, and institutional violence continues in democratic regimes across African countries, democracy may soon become a political fossil of the past with the advent of authoritarian and centralised forms of governance which could worsen the political, economic, and social conditions of many African countries.