By Jeremiah Aminu

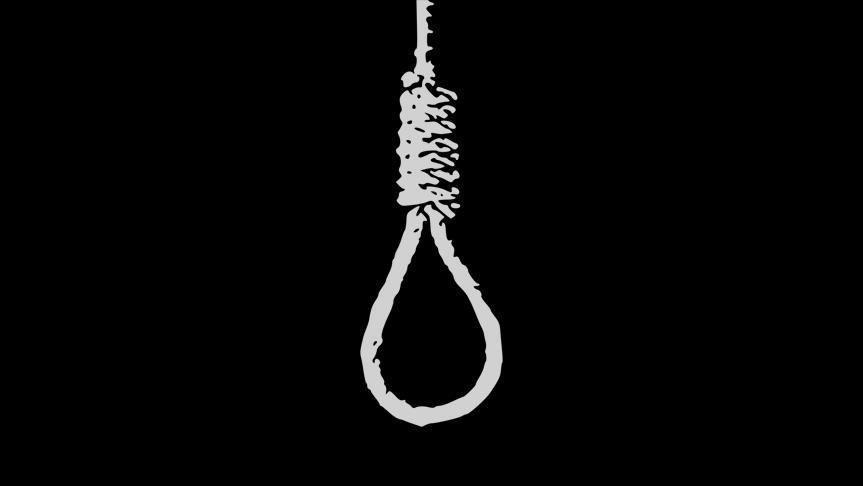

Jacob was horror-stricken as he gazed at the dangling body of his friend, Ayo, swaying left and right on a noose like a clock’s pendulum. His feet were outstretched, his arms freely dancing alongside his lifeless body; his head arched forward with the noose buried deep in his gullet. His eyes were white with emptiness, and his breathless mouth was frozen in a final gasp, spittle drooling from the corner of his lips.

Before his suicide, Ayo had hinted at it in his online chats with Jacob. He often sent stickers of people hanging from nooses, jumping from tall buildings, or rocking themselves with arms wrapped around their knees in dark corners. Each time Jacob asked what was wrong, Ayo would reply: “It’s nothing. I am a man. It’s something I can handle.” Then he would log off and refuse calls for the rest of the day. Now, the signs Jacob once overlooked had come to a tragic end. Ayo had committed suicide.

Ayo’s death in this short story reflects the growing threat of suicide across society. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), over 700,000 people die by suicide every year, and the toll keeps rising. More troubling is the stark gender paradox: while women are more likely to attempt suicide, men are four times more likely to die from it. Studies, including those cited by VeryWellMind, show that men often resort to more lethal methods such as firearms, hanging, or suffocation, whereas women are more likely to use pills, self-poisoning, or less immediately fatal methods. This raises crucial questions: Why do men die more, despite women attempting suicide more often? And why do men tend to choose more violent methods of self-inflicted death?

The answer lies partly in the societal construction of masculinity. To be masculine often means to pose like a tall building, even as one’s foundations are cracking. It means suppressing tears for fear of being seen as “weak,” even when economic, familial, and societal pressures hold a sharp knife to one’s throat. Masculinity implies being one’s own therapist, because seeking help signals vulnerability. Men are programmed to be silent, to muzzle their emotions, to deny help even when drowning. And when life becomes unbearable, many see suicide as the only escape, choosing methods that reinforce their perceived toughness even in death.

Another factor is the stigma of failure. Men are expected to “take charge” as fathers, husbands, or first sons. When they lose jobs, plunge into debt, or are told repeatedly that they are failures, many sink into depression. Unable to meet society’s rigid expectations of success, they often decide to end their lives rather than face perceived disgrace.

So, what can be done to stem this rising tide?

First, society needs a reorientation of masculinity. Governments and NGOs should run programmes that challenge harmful stereotypes of toughness, aggressiveness, and emotional silence. Men must be encouraged to express their emotions and seek help without fear of being labelled weak.

Second, men themselves must build support systems. Brotherhood groups can serve as safe havens for those who still view therapy with suspicion. In such spaces, men can share their struggles without ridicule, creating bonds strong enough to pull them back from the brink when suicidal thoughts arise.

Ultimately, we all have a role to play. As you read this, a man somewhere may have just ended his life, while another hovers at the edge. The urgency is undeniable. When you see a man drowning in depression or burdened by society’s expectations, do not push him deeper into despair. Instead, reach out with love, empathy, and understanding.

We all have a role to play in engendering change to reduce the rising rate of suicide among men. And that change begins with you.