In a historic world first, scientists in Britain have successfully used living human brain tissue to mimic the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, marking a major step forward in the urgent quest for a cure.

A research team at the University of Edinburgh, working in partnership with NHS surgeons, exposed healthy brain tissue from living patients to toxic forms of amyloid beta, a protein heavily linked to Alzheimer’s. By doing so, they were able to observe in real-time how the disease attacks and disrupts critical brain cell connections.

The method offers a rare and powerful opportunity to watch Alzheimer’s develop at the cellular level, paving the way for faster and more accurate drug testing. Experts have hailed the breakthrough as a transformative leap that could significantly boost the chances of finding effective treatments for the disease, which is forecast to affect nearly 153 million people globally by 2050.

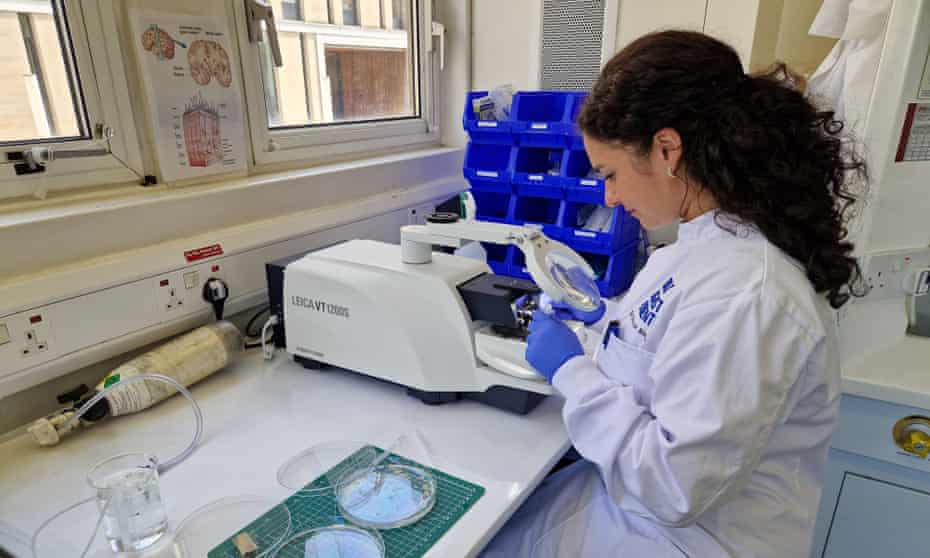

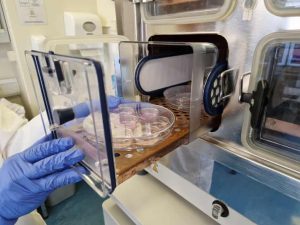

Tiny fragments of healthy brain tissue were collected from consenting cancer patients undergoing surgery at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. Normally discarded after operations, the tissue was instead quickly preserved in oxygenated artificial spinal fluid and rushed by taxi to nearby laboratories, where scientists immediately began experiments.

“We pretty much ran back to the lab,” said Dr. Claire Durrant, a Race Against Dementia fellow and emerging leader at the UK Dementia Research Institute. “And then we start experiments almost straight away.”

At the lab, the brain tissue was sliced into pieces less than a third of a millimeter thick and kept alive in nutrient-rich fluid at body temperature. Researchers then exposed the living brain slices to a toxic form of amyloid beta extracted from Alzheimer’s patients who had passed away.

Their findings were striking. Unlike exposure to normal forms of the protein, the brain cells showed no signs of attempting to repair the damage caused by the toxic variant. Even slight changes in amyloid beta levels, either up or down, were enough to disrupt healthy brain function, indicating that the brain relies on a delicate balance of the protein to operate correctly.

“We believe this tool could help accelerate findings from the lab into patients, bringing us one step closer to a world free from the heartbreak of dementia,” Durrant said.

Further observations revealed that brain slices taken from the temporal lobe, a region known to be impacted early in Alzheimer’s, released higher levels of tau, another protein heavily involved in the progression of the disease. This discovery may help explain why certain parts of the brain are more vulnerable in the early stages of Alzheimer’s.

The groundbreaking study was supported by Race Against Dementia, a charity founded by racing legend Sir Jackie Stewart, and received a £1 million donation from the James Dyson Foundation.

James Dyson himself praised the research as progress “towards solving one of the most devastating problems of our time.”

“Working with brain surgeons and their consenting patients to collect samples of living human brain and keep them alive in the lab is a groundbreaking method,” Dyson said. “It allows researchers to better examine Alzheimer’s disease on real human brain cells rather than relying on animal substitutes.”

Leading dementia experts have also lauded the innovation. Professor Tara Spires-Jones of the UK Dementia Research Institute called it “an important development,” adding that studying live human tissue in real time provides a vital new tool for understanding and ultimately treating Alzheimer’s disease.

The fight against dementia, a disease that devastates millions of families worldwide, may have just gained a powerful new weapon.